On 23 December, 2021, a curious tweet appeared on the internet:

It appeared under the Twitter handle of Dr Thomas Oxley; a neurologist and CEO of Australian neurotechnology company, Synchron.

But the tweet didn’t come from Dr Oxley – it was instead streamed directly from the brain of a man named Philip O’Keefe, 62, living in regional Victoria.

“My hope is that I'm paving the way for people to tweet through thoughts phil” Philip added in a follow-up message.

Philip’s tweet quickly caught fire, with users stunned at how he’d manage to tweet through thought.

“Hi Philip, how do you control which thoughts are typed?” one Twitter user replied.

“Amazing. Hello Matrix, ” wrote another.

To understand how Philip became the first person in the world to tweet directly using nothing but his mind, we have to jump back to 2015.

In May of that year, Philip was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND), a terminal and progressive disease that attacks the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, with respiratory muscle weakness occurring eventually in everyone with the disease.

“One of the first things that I lost was my fine motor skills. The ability to hold a pen, type on the keyboard, tap on a phone is very, very limited, ” Philip told Insight.

“Communication to the outside world is disappearing.”

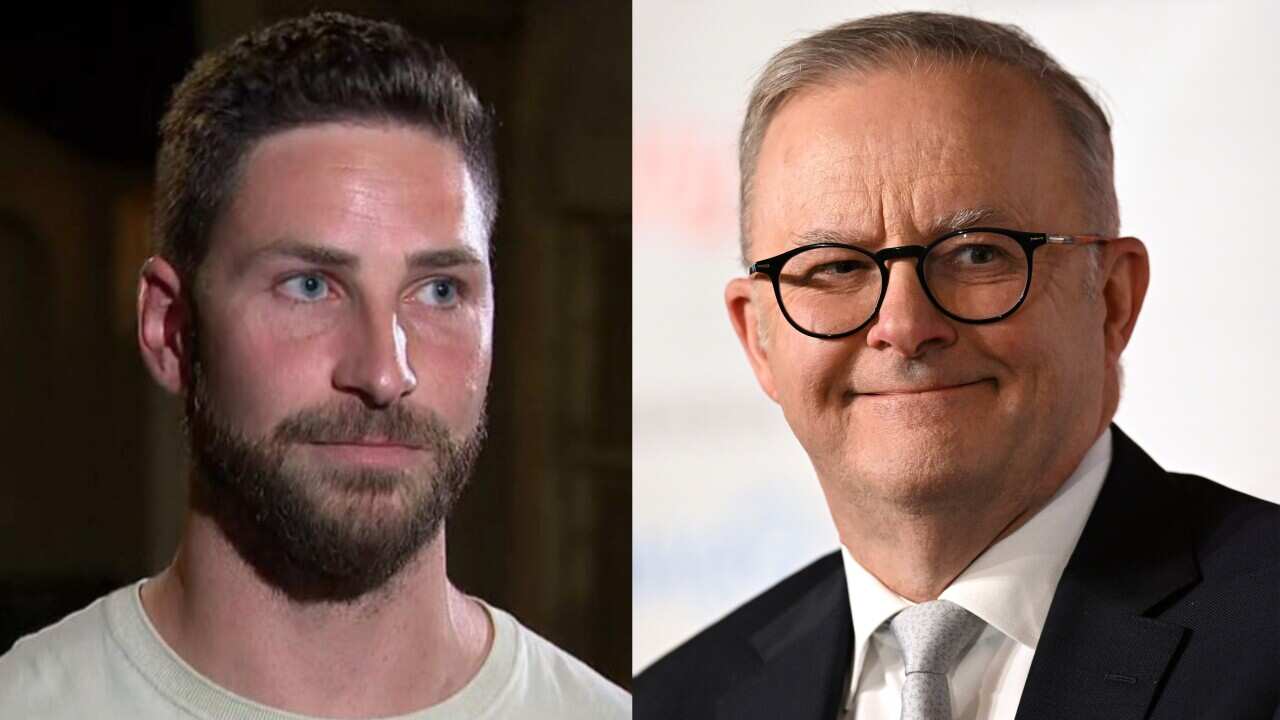

A photo of Philip O'Keefe and his family.

“He jumped at the opportunity to be of any assistance given his terminal outcome,” Philip’s wife Trish told Insight.

Philip was only the second person in the world to be implanted with the technology, and the trial came with risks.

“The actual operation or procedure could be life-threatening at the time,” Trish said.

Philip’s device, called the Stentrode device, reads his brain signals and transmits them to a computer.

The technology is called the ‘Stentrode device’ and is inserted into a vein that sits just under the skull at the top of his head. The technology reads Philip’s brain signals and wirelessly transmits them to a computer which then turns them into commands on the screen, such as click and drag.

He’s been able to send texts, emails and scroll the web using just the power of his thoughts. And, in the process, restore some of the independence stolen by his MND.

“We were awestruck. We thought it was AI and something out of Star Trek, ” Trish told Insight.

The technology Philip is using falls under an umbrella term of BCI, or brain computer interface.

With this investment will come more human clinical trials, and whilst Philip’s experience has been overwhelmingly positive, it’s not always the case for everyone who merges their brain with technology.

Hannah Galvin, 33, who lives in northern Tasmania, has lived with chronic epilepsy for the majority of her adult life. The uncertain nature of not knowing when she was going to have a seizure has had a debilitating effect on her,

“I've ended up with a lot of bruising on my legs. I rolled my shoulder out. My brain just wasn't working as well as it should be, ” she said.

In the process, it’s stolen her ability to do other things she loved in life, like dancing.

Hannah’s epilepsy prevented her from pursuing her passions, like ballet.

Her implant was developed to read her neural activity to predict when she was about to have a seizure.

Scientifically, the trial was successful. But because the technology was so accurate, it discovered that Hannah was having over 100 seizures a day.

Hannah after the operation to implant a device in her brain.

“I would constantly have this bright red light going off,” she told Insight.

“I kept getting the red, brighter and brighter.”

Hannah had often tried to hide her epilepsy in her younger years, and now this technology was reminding her up to 100 times a day of when she was having a seizure.

“If I had have listened to the device, I would practically just spend my life in hospital, ” she said.

“It played with my mind so much.”

Frederic Gilbert, a bio-ethicist from the University of Tasmania who interviews people with technology implanted in their brains as part of his research, says Hannah’s case raises some of the complicated questions that come with merging the human brain with technology.

“We have observed that even if the technology is successful, effective and working perfectly well, there can be psychological rejection,” he told Insight.

“You have a loss of agency.”

Gilbert says that often it’s these ethical questions which pop up after the innovation has taken place.

“With the brain – something as central for someone's identity, sense of their self – I think, it would be quite crucial to have ethics involved early, as soon as possible.”

As technology advances, further trials commence, and more people altruistically put their brains on the line for science, Frederic notes that: “I think the line we need to walk is keeping humans the priority.”

A photo of Philip O'Keefe and his wife Trish on their wedding day.

“It’s a start. Just the start, of a very big journey,” Philip said.

For Hannah, she would never want another piece of technology implanted in her brain.

The solution for her is a peaceful life, technology-free and immersed in the beauty of Tasmania. She still has her very bad seizures.

“But they're just the bad parts of your day. Nothing more than that.”

Watch Insight's episode on